Community Participation is an increasingly popular concept in urban planning. But, too often, participatory initiatives are deployed with haste and without sensitively incorporating diverse community voices into the process. This leads to public mistrust, resentment, apathy, and, at times, agitation. These issues are heightened in unauthorized colonies and urban villages in Delhi, where the line between legal and illegal is blurred, making residents more suspicious of outsiders.

This year, I have had the privilege to work with the Delhi Urban Arts Commission (DUAC) team on a redevelopment proposal for Lado Sarai, an urban village in South Delhi. The team is led by M.N. Ashish Ganju (President at Greha), and our proposal focuses on sewage and sanitation issues, rainwater harvesting systems, and parking schemes. This project is ongoing and the goal is to implement a pilot project for decentralized water and sewage management systems on Old M.B. Road and Shiv Chowk, the oldest mohalla in Lado Sarai.

To successfully implement this project our team is interested in building an ongoing relationship of trust with the community and designing methods to enhance resident’s capacity to drive the development process themselves. The questions we have asked ourselves are: What are the quality of life issues that unite the entire community? How can we reach out to underrepresented demographics? How can we engender participatory monitoring and evaluation of development? By thinking about and answering these questions we have learned several crucial takeaways that will guide the project’s subsequent phases.

Our first learning was that community participation is time consuming. Through various public consultation meetings with residents, we were able to establish trust with the community. Initially response was muted during these consultations. This was partly due to a lack of awareness and fear about issues, such as demolition and evictions, related to illegal/unauthorized development. But through a series of workshops and events – that used easy to understand drawings and pamphlets, and was promoted by the presence of political representatives – we began to hear more voices and get more participation.

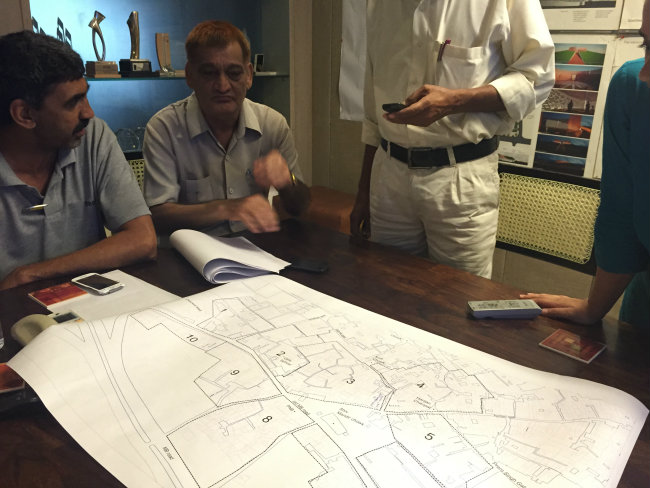

Residents give community leaders input to conduct surveys during a stakeholder meeting.

Our second learning was that despite increased participation some stakeholders were still under-represented, specifically women and youth. The women in the Lado Sarai community were not present at the meetings, because of family responsibilities or norms that limit women’s mobility. To promote youth voices, we developed a painting competition in collaboration with Anurag, a local NGO run school. Thirty students, boy and girls aged 10-14, drew their ideas for Shiv Chowk that included a local community park. The event also provided an environment that was conducive to invite women from surrounding blocks, which gave us the opportunity to capture their opinions on the proposal and quality of life issues in Lado Sarai.

Through community events and information gathering, we also learned that water scarcity and sewage are the biggest issues for the community. These issues bind the community across religion, caste and economic differences. Initially we only proposed improvements for open space and rainwater harvesting, but open drainage, and sewage and rainwater mixing always surfaced in discussions. This led to the inclusion of a decentralized sewage system in the proposal. Because we convened with community members, the main focus of the pilot now addresses the most pressing concerns of Lado Sarai.

Painting competition held in collaboration with a local NGO run school to re-imagine open space and incorporate traditionally under represented voices into the planning process.

To maintain project momentum and longevity, we are now focused on enhancing the skills of active citizens so they can conduct the community surveys required for the pilot’s preparatory work. Ownership and land tenure are unclear in the old city, urban villages and unauthorized colonies. As a result data collection is normally delayed considerably due to difficulties faced on the ground. To address this issue we worked with the community to identify leaders for each block who provided key demographic information. With that information and the support of community leaders, the volunteers and our staff didn’t face strong resistance from occupants when asked to verify information. This maintained project timeline and budgets, reduced hostility towards the project, and marketed the project’s goals for Lado Sarai.

As we move forward there will be more shared learnings. We would enjoy the opportunity to connect with peer organizations interested in different methods and tools that can promote true community participation for the redevelopment of informal settlements. Do write to us, we want to hear your thoughts!